Science-fiction author Harlan Ellison recently passed away, leaving a legacy of work that includes classic episodes of Star Trek and the Outer Limits as well as a dizzying array of novels and short stories. His short story "I Have No Mouth And I Must Scream" was adapted into a PC adventure game in the early 1990s, which maintained the source material's grim view of humanity. Here's our behind-the-scenes look at the game's development, which first appeared in issue #225 of Game Informer.

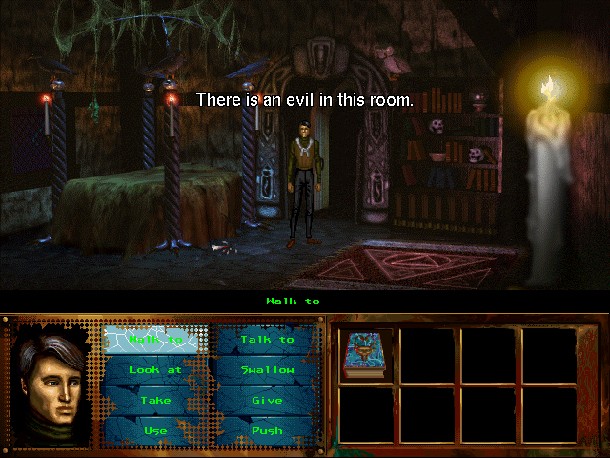

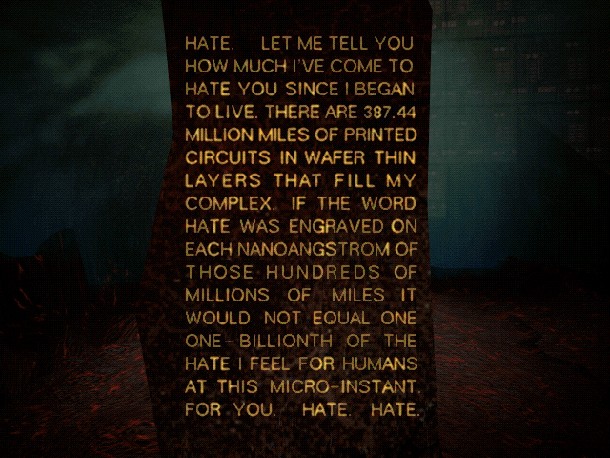

While some younger readers might find it hard to believe, our culture’s interest in post-apocalyptic settings didn’t originate with the Fallout series. Harlan Ellison’s 1967 short story “I Have No Mouth, and I Must Scream,” is an early landmark, offering readers an unimaginably bleak look at humanity’s future, with five desperate souls enduring the constant torture of a deranged AI. Despite its sparse characterization and lack of a traditional narrative, it was adapted into a computer game of the same name in 1995. Here’s the story of how Ellison and a pair of designers transformed the story into one of the most disturbing point-and-click adventure games of all time.

When David Sears heard that publisher Cyberdreams was adapting one of Harlan Ellison’s short stories into a game, the longtime fan’s mind began racing. “I was thinking ‘Oh, it could be ‘Repent, Harlequin! Said the Ticktockman’; or maybe ‘A Boy and His Dog’; and it’s going to be some kind of RPG or something,’ Sears recalls. “And they said, ‘No, it’s ‘I Have No Mouth, and I Must Scream,’ and I was like ‘What?’ At the time, in the game-development community, people said, ‘Oh I love Ellison’s stories, but there’s no way you could turn that into a game.’ I thought, ‘Wow, what have I gotten into?’”

To make the task even more daunting, this was Sears’ first job in game development. Previously, he was a writer and assistant editor at Compute magazine. A feature he wrote on Cyberdreams’ H.R. Geiger collaboration Dark Seed led to a job writing a clue book for the adventure game in the pre-Internet era of 1992, which in turn led to the current offer: Spend a week with the notoriously prickly author Ellison and distill his iconic work – one of the top 10 most reprinted stories in the English language – into his first game-design document.

Finding An In

Finding An In

Sears says that Ellison immediately made him feel welcome. The two talked for a while about Ellison’s writings, science fiction, and other areas of common interest. Sears’ fears of being seen as a fanboy or as being ignorant were unfounded. “I don’t want to damage his reputation, because I’m sure he spent decades building it up, but he’s a real rascal with a heart of gold – but he doesn’t tolerate idiots,” Sears says.

Now came the tough part: turning a tale set in a hopeless world featuring five characters with no real histories into something playable. The story ends with four of the characters dead, with the remaining survivor transformed into a shapeless mass of goo (see sidebar). Super Mario Bros., it wasn’t. The breakthrough came with a simple question. “The question David posed to Harlan that got them started was ‘Why were these people saved? Why did AM decide to save them?’” recalls David Mullich, who produced the game. Ellison was put off by the question, which he told Sears he’d never been asked before. Realizing they were onto something, the pair began working on their concept. The story would be split into five vignettes, each based on one of characters.

“That was going to be the premise of the game – finding out why these characters had been chosen by AM to be tortured and resurrected endlessly and forever,” Sears says. “And then he immediately sat down and started typing on his Olympic manual typewriter.”

Over the next few days, Ellison and Sears began fleshing out each of the five characters, creating deeper histories for them and delving into why they were selected. “I went to work, and I started making my notes, but he had to go first and come up with a premise,” Sears says.

“Harlan wanted to touch on controversial themes,” Mullich recalls. “Each one dealt with a very strong theme.” Some of the issues the game explored included the nature of guilt, sexual assault, and, perhaps most famously, the Holocaust. It was an early attempt to tackle genuinely mature subject matter in an era where “mature” typically meant showing a heroine in a bra.

Since Ellison was responsible for steering the adaptation’s creative direction, Sears found himself with free time in that first week while he waited for Ellison’s notes. The writer would offer Sears distractions, such as recommending that he go out onto the home’s balcony and enjoy the view. When those didn’t work, Ellison dug into Sears’ interests. “What do you like to read? Do you like comics?” Sears recalls Ellison asking, with Sears replying that he liked Neil Gaiman’s Sandman series. “Dialing from memory he makes a call and says ‘Hey Neil, this is David, I’m collaborating with him on a game for Cyberdreams. He’s a fan and he’d love to talk to you about your work.’ So Neil Gaiman talked to me for about an hour, straight off the plane from Mississippi.” Later, Sears had lunch with Babylon 5 writer and producer J. Michael Straczynski, and was among the first to see the show’s pilot episode. “Harlan went out of his way to be a great host.”

Of course, there was still plenty of work to do. “I worked with [Ellison’s notes]over the course of a week in collaboration with Harlan to turn out what we both thought was a really, really good design document,” Sears says. “Cyberdreams disagreed, and they said it was just a proposal.” Sears collaborated with Ellison for an additional week before returning home to Mississippi, where he finished his work on the document over the next six weeks.

Shaping The Story

Shaping The Story

Shortly afterward, Mullich, a producer at Cyberdreams, got involved in the project. For him, the opportunity to work with the license was the realization of a dream. “‘I Have No Mouth, and I Must Scream’ is my favorite short story of all time,” he recalls. Coincidentally, Mullich learned about the game during a talk at a gaming industry conference. “There was a presentation there with David Sears and Harlan Ellison talking about this great game that they had developed, and I was in the audience for that. I was thinking at the time ‘Harlan is my favorite short-story writer, this is my favorite short story, and who’s this guy David Sears? I’ve never heard of him before. I should be the one doing this game!’ So that’s how I came into it.”

Mullich whipped Sears’ inaugural work into shape for Cyberdreams. “It wasn’t organized in the way that a typical game design document is. As I went through it, the story was great and I loved how he’d adapted the work, but I could tell that it was overly simplistic. There weren’t enough puzzles in it, there wasn’t enough dialogue, and it wasn’t formatted in a way that would be easy for a programming team to understand it.” It was up to Mullich to meet with Ellison and revise the document. There, he got a dose of the Ellison that fans are more familiar with. Mullich was preparing to give a presentation of an early build of the game on a PC in Ellison’s kitchen. Ellison made a vague gesture toward an outlet, which was hidden under a potted plant, behind a booth. Noticing Mullich’s difficulty in finding it, Ellison muttered, “Another one of the Cyberdreams’ brain trust.”

Fortunately, Mullich was able to establish a friendly working relationship by talking about his desire to make games that were intellectually stimulating, such as his Apple PC game based on The Prisoner television show. That led to a more productive environment.

Mullich would go to Ellison with proposed dialogue, and Ellison would revise it. “He’d come out 20 minutes later with pure gold. And other times he’d leave stuff and I’d say Harlan, this is terrible. You can do better than this. He’d go ‘Ack, you’re right,’ and he’d go back and revise it. We established a working relationship of mutual respect where we could criticize each other, which was good. Because there was a lot of creative work I had to do.” Mullich estimates that Ellison wrote about 20 percent of the game’s dialogue, with the remaining 80 percent split evenly between Sears and himself.

Turning It All Into A Game

Turning It All Into A Game

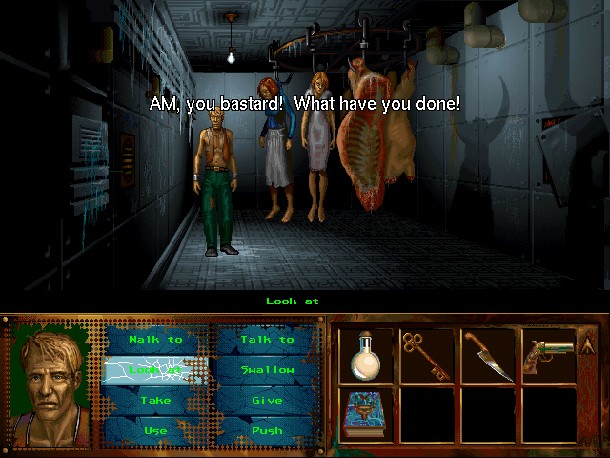

Ellison wasn’t a gamer, which meant that Mullich sometimes had to explain some of the medium’s conventions to the author. One of Gorrister’s puzzles, for example, involved his wife and mother-in-law trapped in a freezer, dangling from meathooks. Gorrister’s story revolved around the character forgiving his family for a string of traumas, and Ellison thought he had come up with a great mind-teaser. “To solve the puzzle you have to let her off the hook,” Mullich remembers Ellison saying. “You metaphorically have to take her off the hook. In order to let it go, you physically have to do that. No one will think of that!” Mullich had to break it to him gently that players were acclimated to doing just that. “Harlan, that’s the first thing that the player is going to do,” Mullich told him. “They go in, they click everything they can, and that’s the first thing they’re going to do.”

Even if Ellison didn’t know much about game design, his pragmatism and flexibility made the process much easier. “The reason he told me [he got involved with the project was] he’d never done a game before and he was interested in taking on the challenge,” Mullich says. “Fortunately he was really good at knowing what was practical and what wasn’t. This far along, he wouldn’t take something that he wasn’t happy with and jettison it completely; he’d try to make adjustments to it and adapt it so that it would work at least a little bit better. He was great to work with.”

Sears had a similar experience when working on the game’s multiple endings. He had to explain to Ellison why players wouldn’t have been satisfied if all paths led to crushing defeat. “OK. This is the thing about games,” he explained. “We can’t have only negative, punishing endings. We can have an optimistic ending. Yeah, we’re giving humanity another shot, but at the same time it’s Harlan’s universe, and there’s every chance these people are going to screw it up again.”

Once the game design was completed, Cyberdreams made the decision to shift development away from its internal team and have Dreamer’s Guild take the reins. Mullich says the studio already had an internal game engine that was appropriate for I Have No Mouth, and I Must Scream, which made the decision easier.

The Aftermath

The Aftermath

The game was published on Halloween, 1995, an appropriate release for a game that dealt with uncomfortably realistic horrors. Critics raved about the game’s often depressing content and the willingness to tackle previously taboo topics. As both Sears and Mullich said time and time again, though the subject matter was gruesome and Ellison was at times notoriously tough to work with, their work on I Have No Mouth, and I Must Scream remains a creative high point in their careers.

Sears, now a creative director at Ubisoft working on the new Rainbow 6 Patriots, actually credits Ellison for his career. About eight weeks after finishing his work with the game, Sears says he got a call from the author. “Hey listen, I’m the keynote speaker at GDC,” Ellison said. “I want you to speak on a panel with me, and I want you to have a job in Los Angeles, because you’re too good to spend your time in Mississippi.”

After finishing the pre-keynote dinner, Ellison took the stage and made an announcement: David Sears was great to work with, and he needed a job. Before Ellison was going to give his presentation, he wanted everyone to bring their business cards up to the stage and put them in a glass fishbowl that he’d brought with him. “And he’s like ‘I’m not kidding,’” Sears says. “‘And after the keynote, David will draw one card from the bowl, and that’s who he will work for.’ I’m pretty comfortable talking in large groups, but at the time not so much. We filled up half the fishbowl, so I had a full Rolodex just for showing up. Three days later I had a job at Virgin Games.

“If he called me today and said, ‘I need you to fix the plumbing in my bathroom,’ I’d be on a plane.”

The Story

The Story

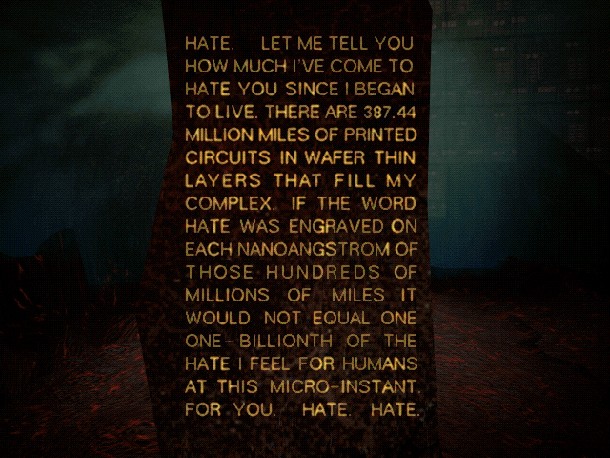

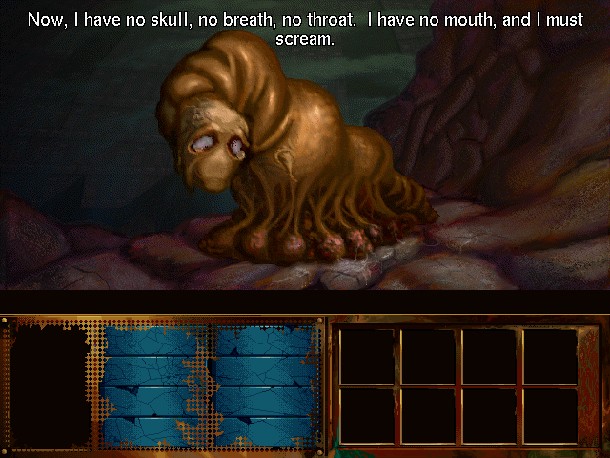

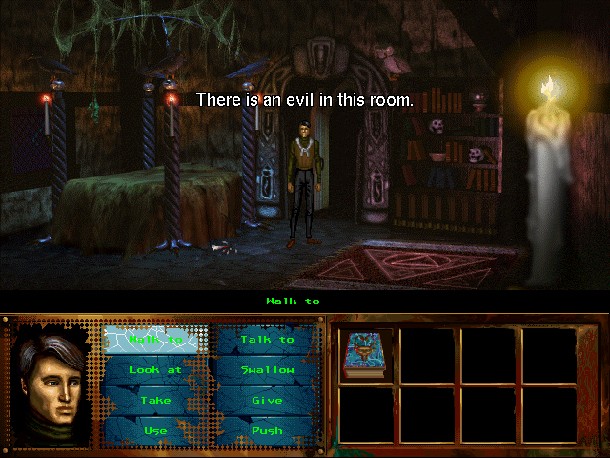

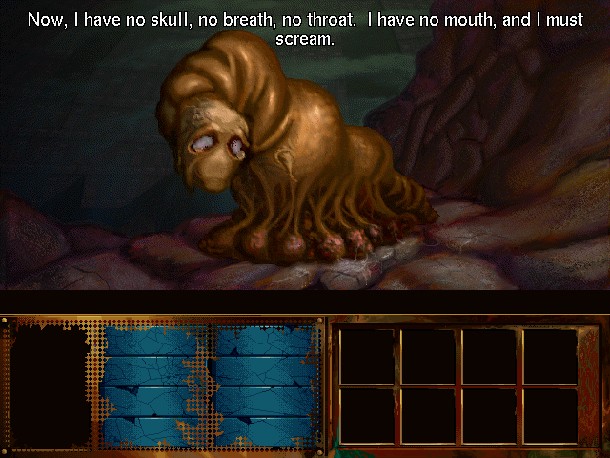

“I Have No Mouth, and I Must Scream” was first published in the magazine If: Worlds of Science Fiction in March 1967. It’s set 109 years after the collapse of human civilization following a war between the U.S., China, and Russia. A group of computers called AM, short for Allied Mastercomputer, became self aware, taking control of the war effort and eliminating everyone on the planet aside from five survivors. Those remaining few have spent the intervening years being continually tortured physically and psychologically by AM. The story concludes with the characters attacking one another after being led on a fruitless hike with the promise of food at journey’s end. When they arrive at their destination, they discover canned goods, but no can opener. The five attack and kill each other, with AM intervening just before the story’s narrator, Ted, is able to take his own life. In retaliation, and to prevent his last plaything from harming himself, AM transforms Ted into a blob of goo. The story ends with the titular line, “I have no mouth, and I must scream.”

The Characters

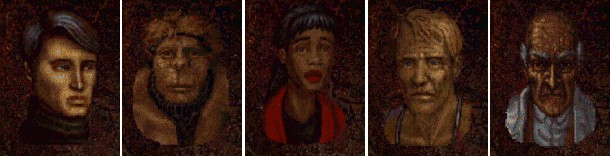

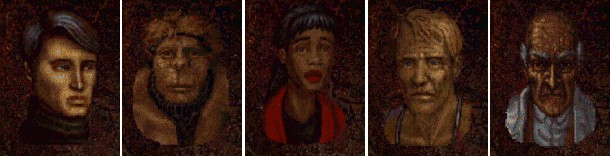

The cast of I Have No Mouth and I Must Scream, from left: Ted, Benny, Ellen, Gorrister, Nimdok

The Characters

To say that adapting the short story into a game was challenging is an understatement. Aside from a few descriptive sentences and skeletal backstories, the story’s five characters are essentially sketches. This is how Harlan Ellison and designers David Sears and David Mullich transformed those stark outlines into fully realized characters with individual plotlines.

Ted

“I remember having some questions about the storyline David Sears had written for Ted, but when I showed it to Harlan, he said that Sears had written a story very different from what they originally discussed,” Mullich says. “However, when I asked him to tell me about the story he and Sears had originally planned for Ted, Harlan said he couldn’t remember it. We discussed several ways of altering the story. Unfortunately I don’t remember any of the details, but I do remember that I made one suggestion that caused Harlan to give me his most cutting insult: ‘You’re thinking like a television producer!’”

Sears’ memories are as foggy as Ellison’s were at the time, though he offers a possible explanation for Ted’s fashion choice of a sweater tied around his neck: “Yuppies were popular at the time.”

Benny

“This was my least favorite of the storylines, although I don’t quite remember why I didn’t much care for it,” Mullich says. Benny’s storyline focused on redemption and forgiveness, as the character found himself haunted by people he betrayed as he explored a brutal tribal society. “Someone recently reminded me that Benny was the character who was the most altered from the original story, in which he was a homosexual scientist. Looking back, I think it might have been a lost opportunity to write a story about someone struggling with the challenges of being homosexual.”

Sears recalls the gay angle, and says that he remembered it being present in his initial draft, even though Benny mentions having a wife. “I believe he was still gay in our version. Even if you have a wife, that doesn’t mean you’re not. It might have been a dropped thread.”

Ellen

“She was tortured. Black women in video games? Someone suffering the psychic fallout of being brutally raped? Again, kind of a groundbreaking character,” Sears says. “I most remember staying up late across several nights and writing the dialogue for the conversation for the confrontation between Ellen and her rapist,” says Mullich. “My infant son was undergoing chemotherapy at that time, and he would have week-long stays in the hospital. I’d stay with him overnight on those occasions, and we’d share the hospital room with another child cancer patient. One time we shared a room with a teenage girl whose chances weren’t good, and she knew it. Once night she woke up terrified and had to speak to a nurse to calm her down. I channeled that memory when trying to imagine the terror Ellen would have gone through in confronting her rapist.”

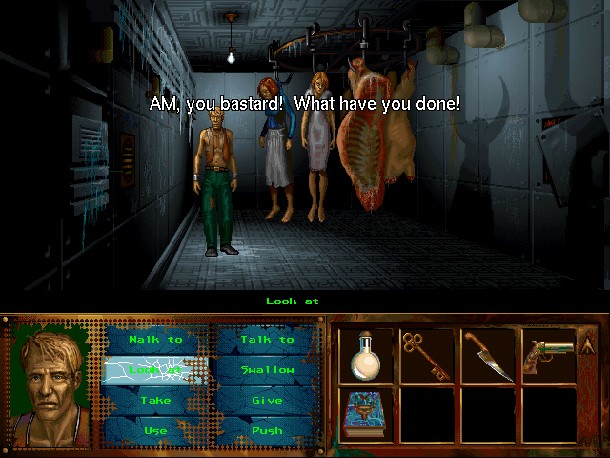

Gorrister

“This was my favorite of the storylines, I loved the artwork – the desert, the iron Zeppelin – and I found the story to be the most metaphorical and dream-like,” says Mullich.

Gorrister’s world was indeed rich with memorable locations, which he navigated while struggling to cope with feelings about his estranged wife.

When asked what he remembers about Gorrister’s storyline, Sears is quick to respond: “Meathooks,” he says, laughing. “I think I’m revealing a little more about how my mind works than I’d intended.” He also remembers an appearance from one of the game’s memorable NPCs, a talking jackal. “I do remember thinking we need a talking head in here, and it ended up being a jackal. I don’t remember if that was Harlan or me.”

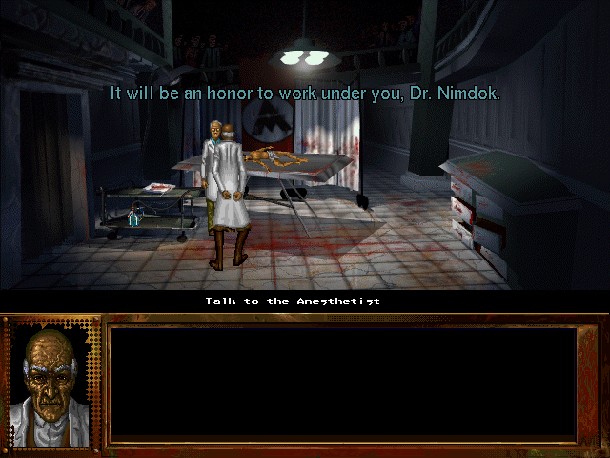

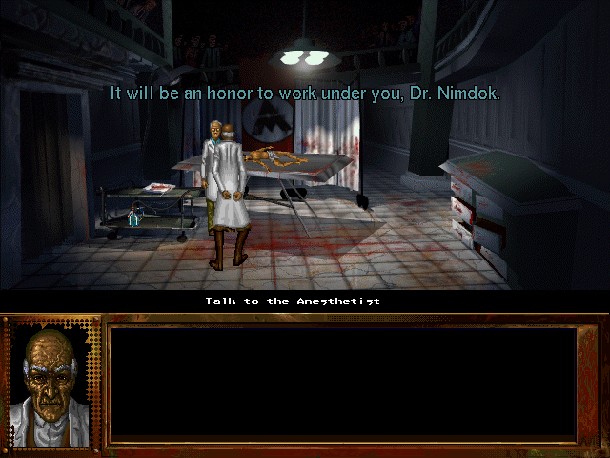

Nimdok

“What I most remember about Nimdok is waiting for the controversy that never came about his story involving the Holocaust,” Mullich recalls. “He was blessed and cursed with a memorable name, and one of the most diabolical back stories,” Sears adds. “Certainly, if we wanted to do something like that [now] we would spend a lot more time defining the lines we wouldn’t cross, careful presentation of this character, and we certainly couldn’t let people know right away what he was. You’d have to build an affinity for him and then we’d slowly reveal these horrors. At the time, we were still on the frontier. The industry was still small enough where publishers would take crazy chances on stuff and see if it stuck.” Some of those crazy chances include allowing the player to take on the role of a Nazi doctor, performing spinal surgery on a child in a concentration camp, and the Holocaust setting itself.

Go here to watch a complete playthrough of the game.

from Game Informer Features https://ift.tt/2ICjkhc